Tentacles

2018 at Premierentage Innsbruck

organised by Christa Pertl and Barbara Unterthurner

Graphic Design by Sebastian Koek

Text by Nina Lucia Groß

»The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.«¹

At the bottom of H. P. Lovecraft’s black sea of eternity sleeps Cthulhu, the age-old monster with the head of an octopus and a bundle of tentacles in his face. In a death-like sleep he rests on the ocean floor and waits there for his time, for the time when the stars will stand just right and he will wake up in order, once again, to subdue the Earth and the human lives on it. Donna Haraway swapped the letters in Lovecraft’s misogynous and racist monster fantasy’s name and brought it back to life as Chthulu. And with her Chthulucene she rung in an age of cross-species and cross-being complicity, an age of tentacular thinking, which always also is a feeling, a fumbling and a trying, an age of beings mourning, composting, felted, fibrous, wandering, drifting.²

In the depths of the not yet known, where Lovecraft envisages the monsters of unclean creatures and the realisation of one’s own transience, leading to madness, Haraway locates the refuge of new stories and symbioses. Where Lovecraft’s narrator warns us against wanting to know too much, against wanting to explore too much, Haraway appeals for a new form of knowledge and research, a form that leaves behind linearity and the human monopoly of thought. The tentacles in Cthulhu’s face, for Lovecraft becoming the symbol of his terribleness, his inhumanness, his all-devouring voraciousness, for Haraway are harbingers of a possible future, a comprehension freed from logic, and a soft, sensitivem approaching.

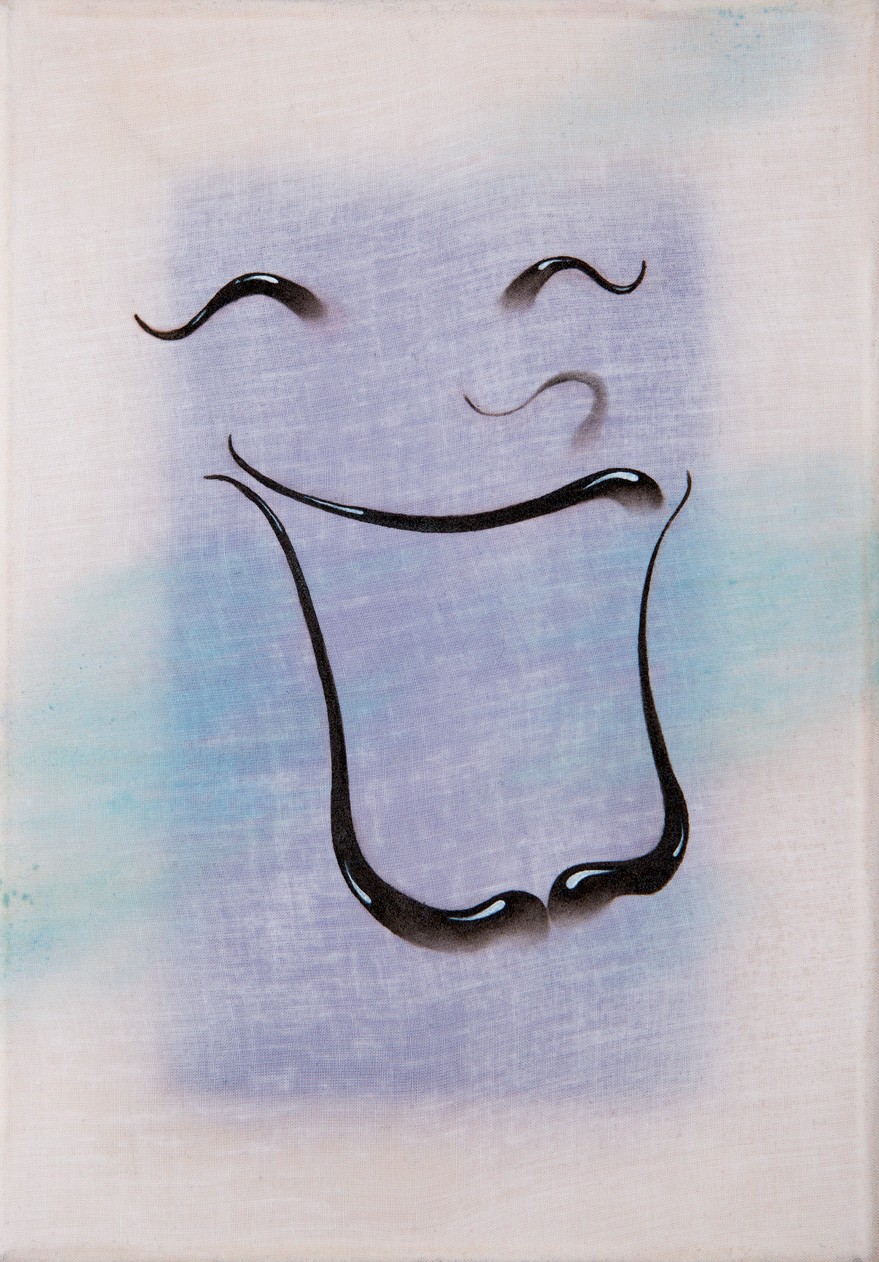

In Sophia Mairer’s painting, measuring 30 by 21 centimetres, depicted on the PREMIERENTAGE poster, the tentacles emerge gleaming and blackly shining into visibility and set the very trap of human perception for us which we walk into with reliable regularity and averageness. When we see clouds, streaks, blots of ink, roots, or tentacles, we automatically see forms, figures, familiar things, recognised things. Most preferably a reflection of ourselves. Something human. Sophia Mairer’s tentacles make us believe we see a face, a grimace, a smile. Is it the emancipatory laught of Medusa, as Hélène Cixous saw it, or the strained smile of the service age, the grin of the entertainer artist, or a snort gone out of control? We, the viewers, are familiar with the rules of pictures and know that what is fixed here for eternity is a moment with a before and an after, that it is a captured moment of visibility. Soon, so our wont illusion goes, the tentacles will go down again and, the illusion tells us again, the face suddenly forming will disappear. All the more, while looking, we cling to the familiarity and the recognition of the form. To meet insecurities and disturbances with fixed interpretations, designations and norms is a well-known strategy.

»All the thousand names are too big and too small; all the stories are too big and too small,« Donna Haraway writes and advises us to stay unsettled, to remain disturbed, to bear ambivalences, streaks, ambiguities, insecurities, the unfamiliar.³ The inability of the human understanding to create a meaningful connection between all things, as diagnosed by Lovecraft, thus, if only the human being at last would cease desperately trying all the time, perhaps indeed could lead to unknown alliances, unforeseeable images and new stories.

Tentacles

2018 at Premierentage Innsbruck

organised by Christa Pertl and Barbara Unterthurner

Graphic Design by Sebastian Koek

Text by Nina Lucia Groß

»The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.«¹

At the bottom of H. P. Lovecraft’s black sea of eternity sleeps Cthulhu, the age-old monster with the head of an octopus and a bundle of tentacles in his face. In a death-like sleep he rests on the ocean floor and waits there for his time, for the time when the stars will stand just right and he will wake up in order, once again, to subdue the Earth and the human lives on it. Donna Haraway swapped the letters in Lovecraft’s misogynous and racist monster fantasy’s name and brought it back to life as Chthulu. And with her Chthulucene she rung in an age of cross-species and cross-being complicity, an age of tentacular thinking, which always also is a feeling, a fumbling and a trying, an age of beings mourning, composting, felted, fibrous, wandering, drifting.²

In the depths of the not yet known, where Lovecraft envisages the monsters of unclean creatures and the realisation of one’s own transience, leading to madness, Haraway locates the refuge of new stories and symbioses. Where Lovecraft’s narrator warns us against wanting to know too much, against wanting to explore too much, Haraway appeals for a new form of knowledge and research, a form that leaves behind linearity and the human monopoly of thought. The tentacles in Cthulhu’s face, for Lovecraft becoming the symbol of his terribleness, his inhumanness, his all-devouring voraciousness, for Haraway are harbingers of a possible future, a comprehension freed from logic, and a soft, sensitivem approaching.

In Sophia Mairer’s painting, measuring 30 by 21 centimetres, depicted on the PREMIERENTAGE poster, the tentacles emerge gleaming and blackly shining into visibility and set the very trap of human perception for us which we walk into with reliable regularity and averageness. When we see clouds, streaks, blots of ink, roots, or tentacles, we automatically see forms, figures, familiar things, recognised things. Most preferably a reflection of ourselves. Something human. Sophia Mairer’s tentacles make us believe we see a face, a grimace, a smile. Is it the emancipatory laught of Medusa, as Hélène Cixous saw it, or the strained smile of the service age, the grin of the entertainer artist, or a snort gone out of control? We, the viewers, are familiar with the rules of pictures and know that what is fixed here for eternity is a moment with a before and an after, that it is a captured moment of visibility. Soon, so our wont illusion goes, the tentacles will go down again and, the illusion tells us again, the face suddenly forming will disappear. All the more, while looking, we cling to the familiarity and the recognition of the form. To meet insecurities and disturbances with fixed interpretations, designations and norms is a well-known strategy.

»All the thousand names are too big and too small; all the stories are too big and too small,« Donna Haraway writes and advises us to stay unsettled, to remain disturbed, to bear ambivalences, streaks, ambiguities, insecurities, the unfamiliar.³ The inability of the human understanding to create a meaningful connection between all things, as diagnosed by Lovecraft, thus, if only the human being at last would cease desperately trying all the time, perhaps indeed could lead to unknown alliances, unforeseeable images and new stories.

Tentacles

2018 at Premierentage Innsbruck

organised by Christa Pertl and Barbara Unterthurner

Graphic Design by Sebastian Koek

Text by Nina Lucia Groß

»The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.«¹

At the bottom of H. P. Lovecraft’s black sea of eternity sleeps Cthulhu, the age-old monster with the head of an octopus and a bundle of tentacles in his face. In a death-like sleep he rests on the ocean floor and waits there for his time, for the time when the stars will stand just right and he will wake up in order, once again, to subdue the Earth and the human lives on it. Donna Haraway swapped the letters in Lovecraft’s misogynous and racist monster fantasy’s name and brought it back to life as Chthulu. And with her Chthulucene she rung in an age of cross-species and cross-being complicity, an age of tentacular thinking, which always also is a feeling, a fumbling and a trying, an age of beings mourning, composting, felted, fibrous, wandering, drifting.²

In the depths of the not yet known, where Lovecraft envisages the monsters of unclean creatures and the realisation of one’s own transience, leading to madness, Haraway locates the refuge of new stories and symbioses. Where Lovecraft’s narrator warns us against wanting to know too much, against wanting to explore too much, Haraway appeals for a new form of knowledge and research, a form that leaves behind linearity and the human monopoly of thought. The tentacles in Cthulhu’s face, for Lovecraft becoming the symbol of his terribleness, his inhumanness, his all-devouring voraciousness, for Haraway are harbingers of a possible future, a comprehension freed from logic, and a soft, sensitivem approaching.

In Sophia Mairer’s painting, measuring 30 by 21 centimetres, depicted on the PREMIERENTAGE poster, the tentacles emerge gleaming and blackly shining into visibility and set the very trap of human perception for us which we walk into with reliable regularity and averageness. When we see clouds, streaks, blots of ink, roots, or tentacles, we automatically see forms, figures, familiar things, recognised things. Most preferably a reflection of ourselves. Something human. Sophia Mairer’s tentacles make us believe we see a face, a grimace, a smile. Is it the emancipatory laught of Medusa, as Hélène Cixous saw it, or the strained smile of the service age, the grin of the entertainer artist, or a snort gone out of control? We, the viewers, are familiar with the rules of pictures and know that what is fixed here for eternity is a moment with a before and an after, that it is a captured moment of visibility. Soon, so our wont illusion goes, the tentacles will go down again and, the illusion tells us again, the face suddenly forming will disappear. All the more, while looking, we cling to the familiarity and the recognition of the form. To meet insecurities and disturbances with fixed interpretations, designations and norms is a well-known strategy.

»All the thousand names are too big and too small; all the stories are too big and too small,« Donna Haraway writes and advises us to stay unsettled, to remain disturbed, to bear ambivalences, streaks, ambiguities, insecurities, the unfamiliar.³ The inability of the human understanding to create a meaningful connection between all things, as diagnosed by Lovecraft, thus, if only the human being at last would cease desperately trying all the time, perhaps indeed could lead to unknown alliances, unforeseeable images and new stories.

Tentacles

2018 at Premierentage Innsbruck

organised by Christa Pertl and Barbara Unterthurner

Graphic Design by Sebastian Koek

Text by Nina Lucia Groß

»The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.«¹

At the bottom of H. P. Lovecraft’s black sea of eternity sleeps Cthulhu, the age-old monster with the head of an octopus and a bundle of tentacles in his face. In a death-like sleep he rests on the ocean floor and waits there for his time, for the time when the stars will stand just right and he will wake up in order, once again, to subdue the Earth and the human lives on it. Donna Haraway swapped the letters in Lovecraft’s misogynous and racist monster fantasy’s name and brought it back to life as Chthulu. And with her Chthulucene she rung in an age of cross-species and cross-being complicity, an age of tentacular thinking, which always also is a feeling, a fumbling and a trying, an age of beings mourning, composting, felted, fibrous, wandering, drifting.²

In the depths of the not yet known, where Lovecraft envisages the monsters of unclean creatures and the realisation of one’s own transience, leading to madness, Haraway locates the refuge of new stories and symbioses. Where Lovecraft’s narrator warns us against wanting to know too much, against wanting to explore too much, Haraway appeals for a new form of knowledge and research, a form that leaves behind linearity and the human monopoly of thought. The tentacles in Cthulhu’s face, for Lovecraft becoming the symbol of his terribleness, his inhumanness, his all-devouring voraciousness, for Haraway are harbingers of a possible future, a comprehension freed from logic, and a soft, sensitivem approaching.

In Sophia Mairer’s painting, measuring 30 by 21 centimetres, depicted on the PREMIERENTAGE poster, the tentacles emerge gleaming and blackly shining into visibility and set the very trap of human perception for us which we walk into with reliable regularity and averageness. When we see clouds, streaks, blots of ink, roots, or tentacles, we automatically see forms, figures, familiar things, recognised things. Most preferably a reflection of ourselves. Something human. Sophia Mairer’s tentacles make us believe we see a face, a grimace, a smile. Is it the emancipatory laught of Medusa, as Hélène Cixous saw it, or the strained smile of the service age, the grin of the entertainer artist, or a snort gone out of control? We, the viewers, are familiar with the rules of pictures and know that what is fixed here for eternity is a moment with a before and an after, that it is a captured moment of visibility. Soon, so our wont illusion goes, the tentacles will go down again and, the illusion tells us again, the face suddenly forming will disappear. All the more, while looking, we cling to the familiarity and the recognition of the form. To meet insecurities and disturbances with fixed interpretations, designations and norms is a well-known strategy.

»All the thousand names are too big and too small; all the stories are too big and too small,« Donna Haraway writes and advises us to stay unsettled, to remain disturbed, to bear ambivalences, streaks, ambiguities, insecurities, the unfamiliar.³ The inability of the human understanding to create a meaningful connection between all things, as diagnosed by Lovecraft, thus, if only the human being at last would cease desperately trying all the time, perhaps indeed could lead to unknown alliances, unforeseeable images and new stories.

Tentacles

2018 at Premierentage Innsbruck

organised by Christa Pertl and Barbara Unterthurner

Graphic Design by Sebastian Koek

Text by Nina Lucia Groß

»The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.«¹

At the bottom of H. P. Lovecraft’s black sea of eternity sleeps Cthulhu, the age-old monster with the head of an octopus and a bundle of tentacles in his face. In a death-like sleep he rests on the ocean floor and waits there for his time, for the time when the stars will stand just right and he will wake up in order, once again, to subdue the Earth and the human lives on it. Donna Haraway swapped the letters in Lovecraft’s misogynous and racist monster fantasy’s name and brought it back to life as Chthulu. And with her Chthulucene she rung in an age of cross-species and cross-being complicity, an age of tentacular thinking, which always also is a feeling, a fumbling and a trying, an age of beings mourning, composting, felted, fibrous, wandering, drifting.²

In the depths of the not yet known, where Lovecraft envisages the monsters of unclean creatures and the realisation of one’s own transience, leading to madness, Haraway locates the refuge of new stories and symbioses. Where Lovecraft’s narrator warns us against wanting to know too much, against wanting to explore too much, Haraway appeals for a new form of knowledge and research, a form that leaves behind linearity and the human monopoly of thought. The tentacles in Cthulhu’s face, for Lovecraft becoming the symbol of his terribleness, his inhumanness, his all-devouring voraciousness, for Haraway are harbingers of a possible future, a comprehension freed from logic, and a soft, sensitivem approaching.

In Sophia Mairer’s painting, measuring 30 by 21 centimetres, depicted on the PREMIERENTAGE poster, the tentacles emerge gleaming and blackly shining into visibility and set the very trap of human perception for us which we walk into with reliable regularity and averageness. When we see clouds, streaks, blots of ink, roots, or tentacles, we automatically see forms, figures, familiar things, recognised things. Most preferably a reflection of ourselves. Something human. Sophia Mairer’s tentacles make us believe we see a face, a grimace, a smile. Is it the emancipatory laught of Medusa, as Hélène Cixous saw it, or the strained smile of the service age, the grin of the entertainer artist, or a snort gone out of control? We, the viewers, are familiar with the rules of pictures and know that what is fixed here for eternity is a moment with a before and an after, that it is a captured moment of visibility. Soon, so our wont illusion goes, the tentacles will go down again and, the illusion tells us again, the face suddenly forming will disappear. All the more, while looking, we cling to the familiarity and the recognition of the form. To meet insecurities and disturbances with fixed interpretations, designations and norms is a well-known strategy.

»All the thousand names are too big and too small; all the stories are too big and too small,« Donna Haraway writes and advises us to stay unsettled, to remain disturbed, to bear ambivalences, streaks, ambiguities, insecurities, the unfamiliar.³ The inability of the human understanding to create a meaningful connection between all things, as diagnosed by Lovecraft, thus, if only the human being at last would cease desperately trying all the time, perhaps indeed could lead to unknown alliances, unforeseeable images and new stories.

1 Howard Phillips Lovecraft, »The Call of Cthulhu,« 1928

2,3 Cf. Donna Haraway, »Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capi-talocene, Chthulucene,« 2016

1 Howard Phillips Lovecraft, »The Call of Cthulhu,« 1928

2,3 Cf. Donna Haraway, »Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capi-talocene, Chthulucene,« 2016

1 Howard Phillips Lovecraft, »The Call of Cthulhu,« 1928

2,3 Cf. Donna Haraway, »Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capi-talocene, Chthulucene,« 2016

1 Howard Phillips Lovecraft, »The Call of Cthulhu,« 1928

2,3 Cf. Donna Haraway, »Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capi-talocene, Chthulucene,« 2016

1 Howard Phillips Lovecraft, »The Call of Cthulhu,« 1928

2,3 Cf. Donna Haraway, »Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capi-talocene, Chthulucene,« 2016